Raise your hand if you’ve ever had an anxiety dream about a concert where you had a memory lapse.

Yup, thought so. Is there any aspect of performing that stresses musicians out this much?

When I was a student, I thought I was great at memorization. This was my method:

- Put a CD of the piece I wanted to memorize on repeat play for a few hours every day.

- Run the piece five or six times a day so that what I thought of as my “muscle memory” would learn the piece for me.

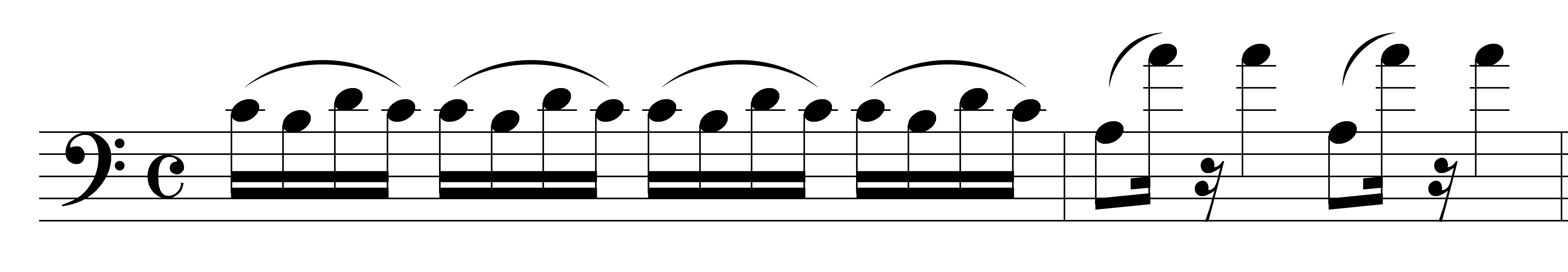

I got away with this for a surprisingly long time. Then came the day I had to perform Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata by memory for my studio class. All was going well until I started the second theme, and I played this:

It sounded completely wrong. What was going on? My fingers knew the theme back to front. I felt a surge of panic rising in my chest as the pianist paused and stared at me. I tried again. It sounded wrong again. What on earth…?

That was when I realized I’d been playing the theme in A major, which is the key it’s in at the recapitulation — except that I was only in the exposition, where it’s supposed to appear in the key of C major.

I fumbled and scrambled until I recovered and was able to continue, but the memory of the mistake mortifies me almost two decades later.

Here’s why my memorization method didn’t work.

- “Muscle memory” is a misnomer. Muscles don’t have memories.

- You can only successfully memorize music if you exercise good musicianship. I wasn’t exercising good musicianship, I was being a parrot.

The problem with having one bad memory lapse is that it tends to give you a bit of a complex. I knew that I needed a drastic rethink in my memorization methods. Over many years, I figured out a six-step method that works very well for me and for my cello students at the University of Idaho. I hope it works for you too.

STEP 1: It starts with the score.

The full score, not just the cello part. Memorizing only the cello part would be like an actor playing Romeo memorizing only his own lines without bothering to learn what the actor playing Juliet says back to him.

Before you learn the notes on the instrument, before you even listen to recordings, you should go right to the score — and make sure you get the most scholarly performing edition you can — Henle and Bärenreiter are best for most repertoire.

The full score is like a jigsaw puzzle. It shows you the “big picture” of what you’re trying to accomplish, long before you try to sort all the little pieces into where they belong. Daily full score study uses your eyes, your ears, your voice, and your fingers to memorize music. As Robert Schumann once opined, in his timeless Advice to Young Musicians, “You must get to the point that you can hear music from the page.”

That’s right — you can learn to hear music in your head from reading the score just as easily as you can hear words in your head when you read a novel. Don’t believe me? Watch this scene from the completely fact-based drama, Amadeus, where Mozart’s jealous rival Salieri practises aural skills as he leafs through Mozart’s scores.

If you aren’t quite as good at this as Salieri, help is at hand. If you can’t take a university-level class in theory, analysis, and musicianship skills, there are books and online resources that can help you self-teach these topics, such as (shameless plug #1) this one.

Using a pencil, make the following annotations in the score.

- Large scale structures: what is the form of the piece? Where are the big sections, such as the exposition, development, and recapitulation in a sonata-allegro movement? What are the high and low dynamic and expressive points of the piece?

- Small-scale structures: how are the phrases structured (sentence, period, etc)? Where and what are the themes? First theme, second theme, transitional materials, closing themes, codettas…? How are they connected? What key centers do they go through? Where and how to modulations occur? What are the characteristic intervallic, rhythmic, and harmonic components of the themes? Are repetitions exact or inexact? How do the themes differ melodically, harmonically, or rhythmically when they occur in different sections of the piece?

- For diatonic music, write a complete Roman numeral/figured bass analysis in the score. This will also help for figuring out intonation, which depending on context may be determined by the composer’s voice-leading.

Now, sing through your own part — and everyone else’s, within reason — and conduct yourself. Use a metronome. If you know solfege, use it. (Fixed do vs. moveable do? Doesn’t matter, they’re both great.)

Also? Don’t sing like a robot. Be as expressive as possible right from the get-go. “Notes first, expression later” is a waste of time. Your head and your heart aren’t separate entities. You have to use them both. There’s a reason we call playing from memory “playing by heart.” Expression dictates all the physical parameters of playing, such as fingerings, bowings, shifts, vibrato, and so on. Use it.

STEP 2: Now you can listen to recordings.

Listening to recordings does contribute to the process of memorization — there’s a reason children learning by the Suzuki Method are so good at performing from memory. The problem with this is when you use it to replace proper score study the way I did. The chief benefit of listening is to find inspiration in the interpretations of the great cellists. Listen to as many interpretations possible — don’t just get fixated on one recording to the exclusion of others. The great players are all wildly brilliant and all wildly different from each other. They’re our heritage, they’re our teachers. Learn from them. Go back to the full score. Sing, conduct, interpret, plan.

STEP 3: Pick up the cello, mark up the cello part.

Decide on what physical actions best serve your planned interpretation. In the early stages of note-crunching, you’ll of course want to experiment with lots of possible fingerings and bowings. But once you’ve found good ones, write them down and, for the most part, stick to them. Constantly tinkering with these things is a recipe for disaster. Sure, change a few things here and there if you find something better, just don’t totally revise everything every five seconds.

Know what section you’re in at all times while you’re playing. Know what key you’re in. Know which theme you’re playing. Know when you plan to reach your highest and lowest expressive and dynamic points. Play with as much expression as you can squeeze out of yourself.

Go back to the full score. Sing, conduct, interpret, plan. Notice things you might have missed the first few times, such as accents, dynamics, and other expressive directions.

STEP 4: Think. Think again. Think harder.

After a long practice or score study session, I find it useful to keep the piece ticking over in my mind. Long walks are a good time for post-practice contemplation. As the fresh air fills your lungs, try to hear the piece in your head. If you get stuck, go back to the big picture of the large sections, key structures, and thematic materials. I cannot stress enough how useful this process is.

The next away-from-the-instrument practice method is going to sound very daunting. I was stunned to read in Colin Hampton’s memoir, A Cellist’s Life, that the way he taught his students to memorize music was “to have them write it out from memory first. If they can write it out, they’ll know it.” My first thought on reading this was “I can’t do that!”

The problem with thinking you can’t do something is that the universe doesn’t understand “can’t.” Of course you can do it; you just have to think much harder than you’re used to thinking about the small-scale things you might have skipped over in practice. The metronome markings, exact note and rest values, phrase marks, articulations, dynamics, performance directions, and so on. It’s a chastening feeling when you go back to the score and realize how much you’ve missed. But I can say from personal experience that this is the single most useful method for memorizing music because it really does force you to think extremely hard. Thinking is good.

Go back to the full score. Sing, conduct, interpret, plan, notice. Go back to the cello. Refine your performance.

STEP 5. Practise performing, perform practising.

Sometimes the biggest hurdle we face in performing by memory isn’t the memorizing itself, it’s the fact that we are performing. (Shameless plug #2: performance anxiety is real, people.)

Therefore, make every practice session a performance. (Shameless plug #3: I wrote an entire book about how to do this.) If you can’t get someone to listen to you, make a video recording of yourself playing a section, a movement, or an entire piece from memory. (For some weird reason, this always makes me feel as anxious as having a person in the room — which makes it great practice for the concert stage!)

Listen to your recording, following along with the score, making notes. Practise all the bits you messed up, then re-record. Listen to the second recording. Acknowledge the progress that has taken place (we cellists are so unkind to ourselves!), take a few more notes.

Go for a walk. Keep the piece ticking over in your mind. Go back to the score. Sing, conduct, interpret, plan, notice, practise, perform.

STEP 6. Repeat phases 1-5. (No, really.)

While practising phases 1-5 will create neural pathways in your brain on your journey towards memorizing a piece, the memorization isn’t necessarily permanent. If you want to keep it, you have to repeat it many times. A piece you memorized last year may need a complete rethink in order for you to play it from memory now. Be careful, though. It’s too physically and mentally tiring to set yourself a task such as playing a piece from start to finish six times a day as you attempt to memorize it. Once or twice — as in Step 5 — should be enough.

And then…

Go back to the score… you know the rest.

(c) Miranda Wilson, 2018. No part of this blog post may be reproduced without the permission of the author.

Very good advice. My favorite technique for memorizing — when my material was mostly learned and memorized — was to play along with recordings. A we bit of a cheat, maybe, and not entirely a great idea (in part, for reasons of interpretation), but it works, except of course if the work be new or unrecorded. My issue was always memorizing the parts I DID NOT PLAY… the “rests” of accompaniment between the solo passages. Also, playing along with a recording is helpful for pacing for endurance factors. Again, I think this becomes more important as one approaches performance readiness.

LikeLike